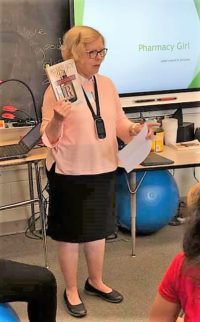

At a school visit, sixth graders had amazing questions about Pharmacy Girl and the process of writing the book. I’d like to share one with you.

At a school visit, sixth graders had amazing questions about Pharmacy Girl and the process of writing the book. I’d like to share one with you.

How did you get all the information for Pharmacy Girl?

Writing a book is a little like writing a gargantuan research paper, but it is loads more fun.

Most rewarding in my research was talking with my family, particularly talking with Aunt Juanita who remembered the most about the Spanish influenza epidemic. She delivered medicine on her scooter and sometimes gave patients their first dose of medicine. My mother remembered washing empty glass prescription bottles to reuse in the store. The story about my mother getting a hold of the gun in the store I heard from my brother. So, my heartfelt advice: Talk to your family now about their stories. Don’t wait.

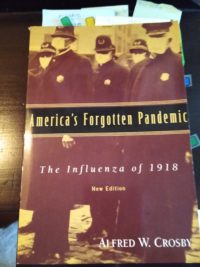

My search for information started by accident when I discovered Alfred Crosby’s America’s Forgotten Pandemic (2003). Here was an answer to my question: Why didn’t family members die from Spanish influenza? Two theories I found in Crosby’s book were 1) possibly family members had immunity from the previous winter’s flu season, and/or 2) good nursing care.

My search for information started by accident when I discovered Alfred Crosby’s America’s Forgotten Pandemic (2003). Here was an answer to my question: Why didn’t family members die from Spanish influenza? Two theories I found in Crosby’s book were 1) possibly family members had immunity from the previous winter’s flu season, and/or 2) good nursing care.

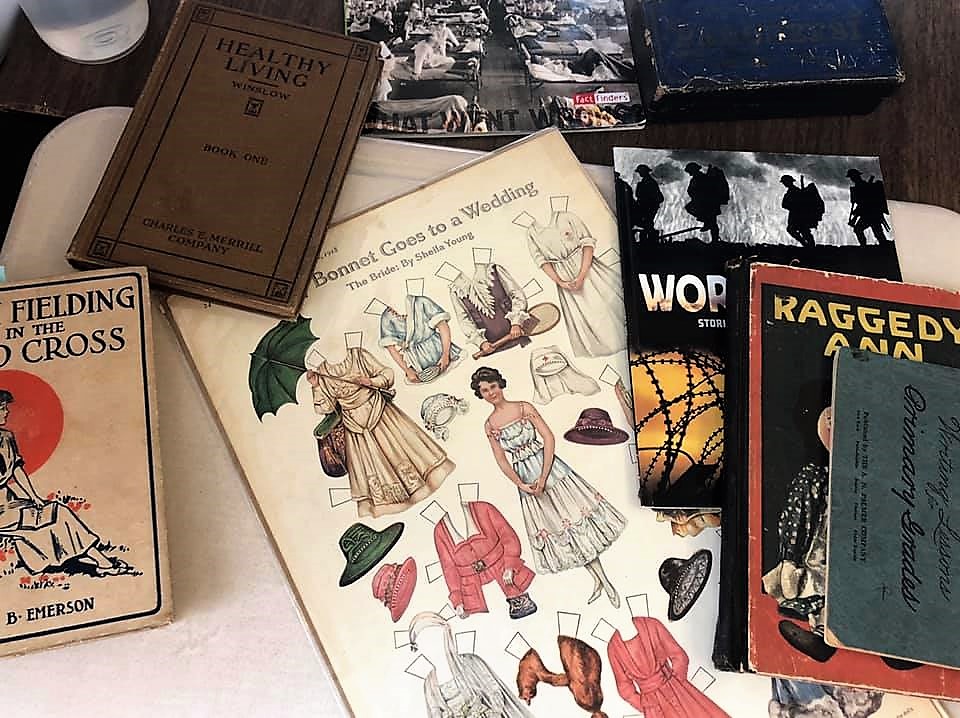

Using E-Bay, I collected a small library of books and magazines printed around 1918. These primary sources included medical and pharmacy books, cookbooks, laundry how-to pamphlets, McCall’s magazines, and original Committee on Public Information (CPI) pamphlets published by the federal government during World War One.

Particularly fun was reading old novels for girls, like the Ruth Fielding Series, to get a feel for how people talked and the words they used. Did you know girls said, “Oh fudge!” to express frustration? Well, probably not when adults were around. Slang was frowned upon. It was inspiring to see how adventurous female characters were one hundred years ago.

Particularly fun was reading old novels for girls, like the Ruth Fielding Series, to get a feel for how people talked and the words they used. Did you know girls said, “Oh fudge!” to express frustration? Well, probably not when adults were around. Slang was frowned upon. It was inspiring to see how adventurous female characters were one hundred years ago.

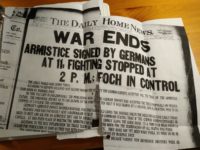

You might say Pharmacy Girl was ripped from the pages of The Daily Home News. Sounds dramatic, but the aforementioned New Brunswick (NJ) newspaper and the New York Times from 1918 both helped drive the plot line. News helped me place characters in the right places at the right times.

False Armistice Reported

Newspapers gave me vivid descriptions of the Fourth Liberty Loan parade, the Gillespie Shell-loading Plant explosion, and the False Armistice. The most poignant piece of writing was a depiction of the Gillespie Explosion. There was no by-line for the article, but I hope the reporter knows how much I appreciated his or her skill and how reading the account touched my heart. On a happier note, a great find was a four-line ad telling readers they could leave sheets and towels for the Red Cross Linen Drive at my grandfather’s drug store in Highland Park and he would gather the donations to take to the Red Cross Room in New Brunswick.

I used the internet to access the New York Times for 1918. That made the writer’s life easy. For the Home News, I drove to New Jersey to use the New Brunswick Free Public Library’s microfilm collection. That experience wasn’t easy, but it sure was entertaining, and being at the library helped me visualize the chase scene at the end of the book. (Update: The Home News is now digitized at the NBFPL.)

As you can imagine, the internet was a storehouse of fascinating information. I found influenza facts on the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) website, and the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library website provided material on “Meatless Mondays” and wartime food conservation. The internet is where I found the picture of the electrified Christmas tree in Washington Square in New York City.

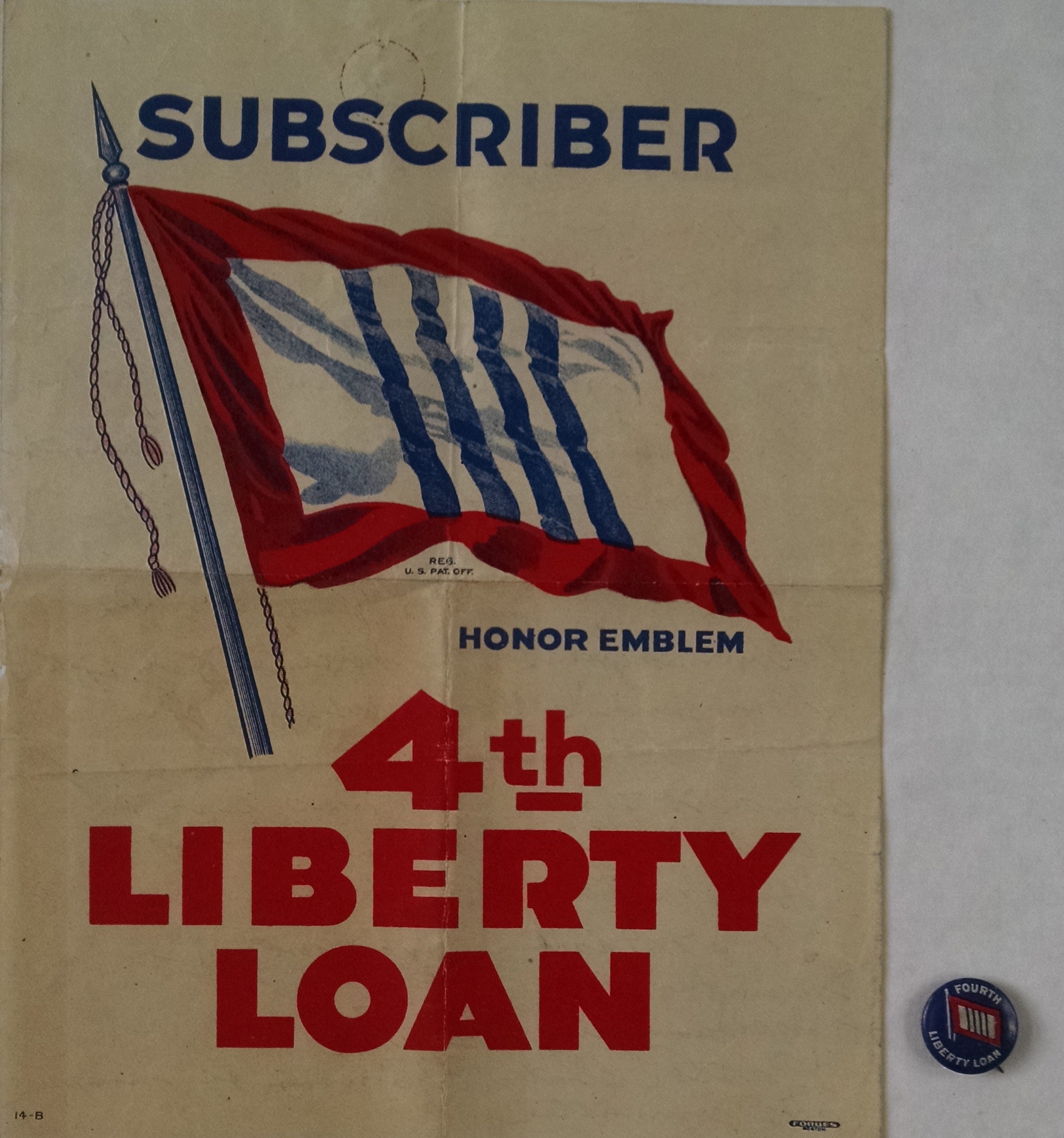

Ephemera, a technical term for “old stuff,” helped me include true-to-life details. Items in my collection include a Fourth Liberty Loan window placard and pin. You may recall that in Pharmacy Girl, Josie gives a placard and a pin to Mr. Horowitz when he buys a Liberty Bond. That is where I got the idea. See below.

One of my favorite pieces is a two-page spread of paper dolls from a 1917 McCall’s magazine. It’s entitled “Betty Bonnet Goes to a Wedding” and includes both the bride and the groom and the clothes they would wear. I found these items on E-Bay.

Another artifact I used in writing the book was a Valentine card sent to my mother when she was a toddler. It depicted a young man winning the heart of a girl with his “Votes for Women” valentine. This made me think that my grandparents favored women’s suffrage. Hooray! This notion of parental support of women’s capabilities was borne out later when my grandparents sent both their daughters to college at the beginning of The Depression, a time when few women went to college, and for those that did, money for education was scarce.

I hope this post helps, in part, to answer the question of how I got my information. Now I wonder, do you have questions I can answer in a future blog? Please write to me. It’s easy. Click here.